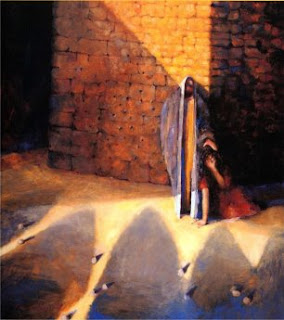

Tom Hanks plays Forrest Gump in Robert Zemeckis' award-winning movie.

Tom Hanks plays Forrest Gump in Robert Zemeckis' award-winning movie.With the latest Roy Morgan and 3News/Reid Research polls reconfirming the extraordinary popularity of John Key’s National-led Government, it is time for the Left to stand back and confront some very hard truths about the New Zealand electorate. For a start, we simply have to resign ourselves to the fact that a very large number of former Labour voters are now convinced that the Right has more to offer them than the Left. How did that happen? And what (if anything) can/should progressive New Zealanders do about it?

NEW ZEALAND is being Forrest Gumped. Like the character in the Tom Hanks movie, the heroes of John Key’s new political order are simple men and women. Confused by complexity and irritated by conflict, they mostly experience politics as a series of random and largely inexplicable events. For them, if I may paraphrase Forrest Gump: "Political life is like a box of chocolates, you never know what you’re gonna get."

International recession, environmental crisis, tax cuts, job losses: the content of the daily news blows in, blows out, like a summer squall. When it rains our Kiwi Forrest Gumps pull on their coats and pull in their heads. When it shines, they shake their coats dry and smile.

Ideas don’t count for much in this new political order. What matters most is the relationship voters form with their leaders. To succeed in today’s electoral environment, a politician must be likeable. The more voters like you, the more they trust you. Labour lost in 2008 because, sometime shortly after the election of 2005, a solid majority of the electorate simply stopped liking and trusting Helen Clark.

Key, on the other hand, has always come across – and continues to present himself – as a thoroughly likeable bloke. People trust him. So much so that, in David Farrar’s latest poll-of-polls, National commands 53.6 percent support, to Labour’s 29.9 percent.

Like I said, we live in simple times.

And hasn’t it always been thus? Haven’t half of humanity always found themselves on the wrong side of life’s great bell curve? We can’t all be blessed with Albert Einstein’s brains, Picasso’s creativity, or Nelson Mandela’s greatness of heart. Harnessing heredity’s meagre legacy to the hard business of making a life for themselves and their loved ones is as much as most folk dare aspire to. And more than a few make a mess of even that.

Were I writing these words in Eighteenth Century England, the mathematical certainty of human mediocrity wouldn’t be a problem. Three hundred years ago, what the "common people" did was a matter of supreme indifference to their rulers.

As Thomas Gray put it, in his Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard:

Far from the madding crowd’s ignoble strife

Their sober wishes never learned to stray;

Along the cool sequester’d vale of life

They kept the noiseless tenour of their way

In our post-modern, consumer-driven, liberal-democratic, capitalist society, however, mediocrity is a very big problem. Why? Because the simplest citizen’s vote carries exactly the same political weight as the most intelligent citizen’s. And the dollars they spend count for just as much, if not more, as the dollars spent by the rich. Modern economies can withstand a cessation of spending by the wealthy few. But, when the numberless, anonymous families who inhabit our suburbs start cutting back, things can go very wrong, very quickly.

And that’s the most terrifying aspect of the 21st Century’s "madding crowd" – the vital role that "ordinary" people’s "self-esteem" now plays in just about everything we do. The moment that post-modern citizens begin to suspect they’re being cheated – or, even worse, condescended to – advanced capitalist societies become highly unstable. Just recall the wrenching political realignment occasioned by Don Brash’s charge that Maori were receiving special privileges. Or what happened when working-class Kiwi parents became convinced that a bunch of childless left-wing politicians was telling them how to raise their kids.

The political empowerment of mediocrity requires that the ideas of the average person, no matter how ill-informed, be accorded exactly the same respect as the ideas of the most learned doctors, scientists and professors. More even. Because why should anybody take seriously the opinions of people who believe they’re smarter and better than everybody else?

While political parties remained strong enough to filter-out the demands of the ignorant and prejudiced, capitalism and progress marched together. The mass parties of the Left were especially important in this regard. As the inheritors of the Enlightenment’s rational scepticism, they kept their poorly paid, poorly housed and poorly educated followers in step with the steady advance of the physical and social sciences.

By the mid-20th Century, however, it had become clear to the political defenders of capitalism that the rational application of science to society’s ills could only end in some form of socialism. Their solution was to turn the latent ignorance and prejudice of the Left’s mass following against both itself and its "elitist", "liberal" and "intellectual" leaders. The Right’s weapons of choice were Race and Religion.

As the American political scientist, Joseph E. Lowndes, argues in his excellent From the New Deal to the New Right: Race and the Southern Origins of Modern Conservatism, by breaking up the social-democratic majority which had emerged from the Great Depression and World War II, and then electorally corralling it – first under the rubric of the "Forgotten Americans", then the "Silent Majority", and finally "Middle America" – the Right was able to install ignorance and prejudice as the prime drivers of contemporary political life.

All of the above terms, says Lowndes, were intended to: "describe a people under attack by an invasive federal government, threatened by crime and social disorder, discriminated against by affirmative action, and compromised by moral and cultural degradation."

The rise of reality television; the full scale assault by creationists and climate-change deniers on settled science; the dumbing-down of practically all forms of journalism and entertainment; and the unceasing disparagement of "academics" and "intellectuals"; all point to the Right’s cynical enthronement of the simple and the stupid as the ultimate arbiters of what is – and what is not – politically possible.

Which is, of course, the central theme of Robert Zemeckis’ hugely popular film. By the light and magic of Hollywood, Forrest Gump, the wise fool, gets to participate in all the seminal moments of recent American history. The film-maker not only ensures the meek inherit the earth, he allows them to utterly falsify and remake it.

Where the American Right has led, our home-grown conservatives have followed. A nation once celebrated for its unparalleled levels of political participation has been taught to scorn the very term. The birthplace of Rutherford has become the spiritual home of climate change denial. The country where progressive ideas once came to be born, has become the place where reactionary ideas go to die.

Proof, perhaps, that when Forrest Gump said "stupid is as stupid does", he knew what he was talking about.

This essay was originally published in The Independent of 23 April 2009.